| Citation: | Please cite this article as: Karan A, Ali AA, Esmail K, Akinjogbin T, Lamsal S, Missov E. Post-op cocaine use resulting in catastrophic cardiovascular compromise. J Geriatr Cardiol 2023; 20(2): 155−158. DOI: 10.26599/1671-5411.2023.02.002. |

Cardiac tamponade can result from a variety of intrapericardial or extrapericardial sources of compression of the heart and great vessels. Cardiac tamponade can be acute or subacute and results from fluid or gas collection in the pericardial space leading to impairment in cardiac function. Postoperative cardiac tamponade following open heart surgery can be caused by hemorrhage within the pericardial sac or by mediastinal hematoma formation.

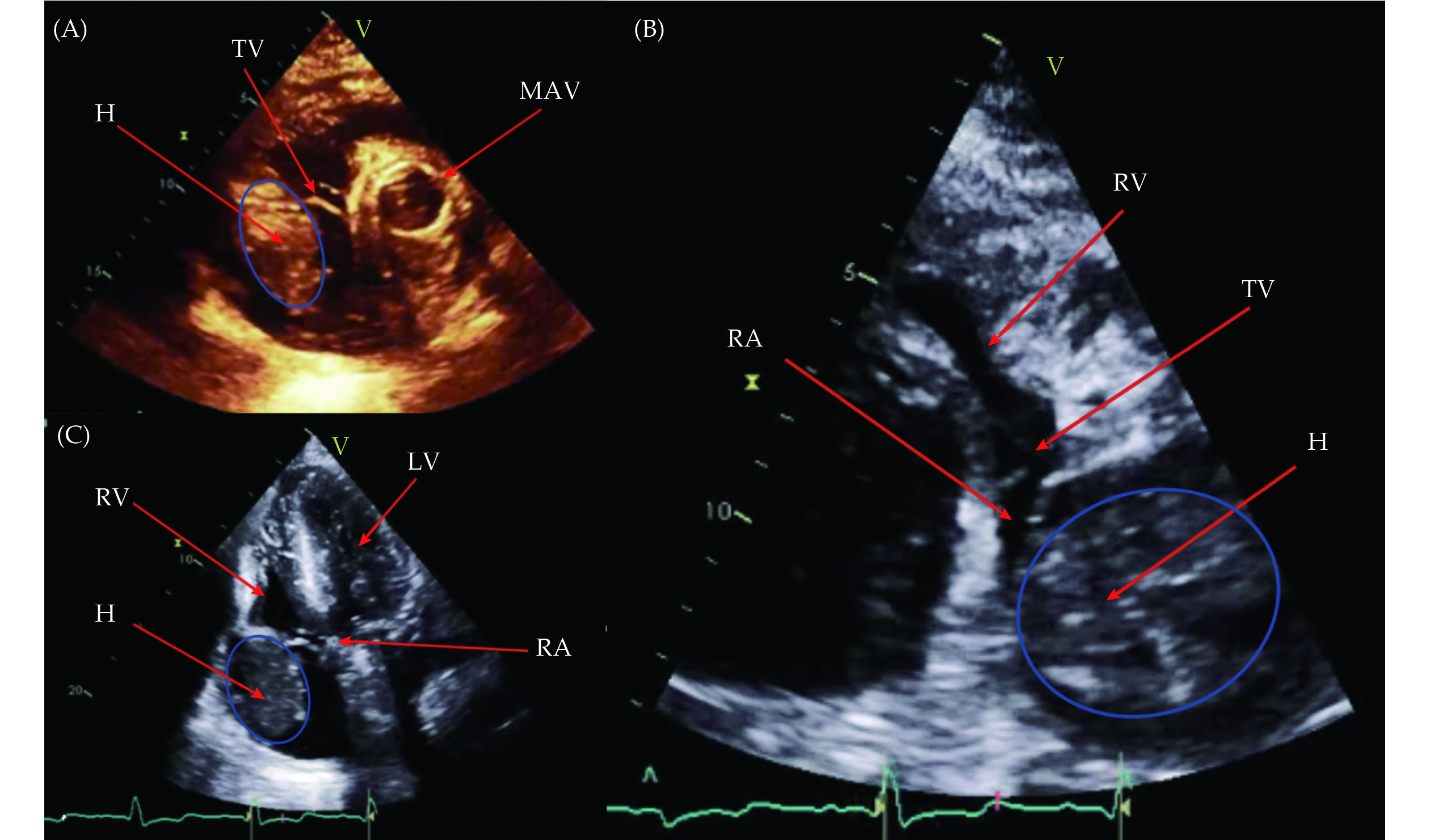

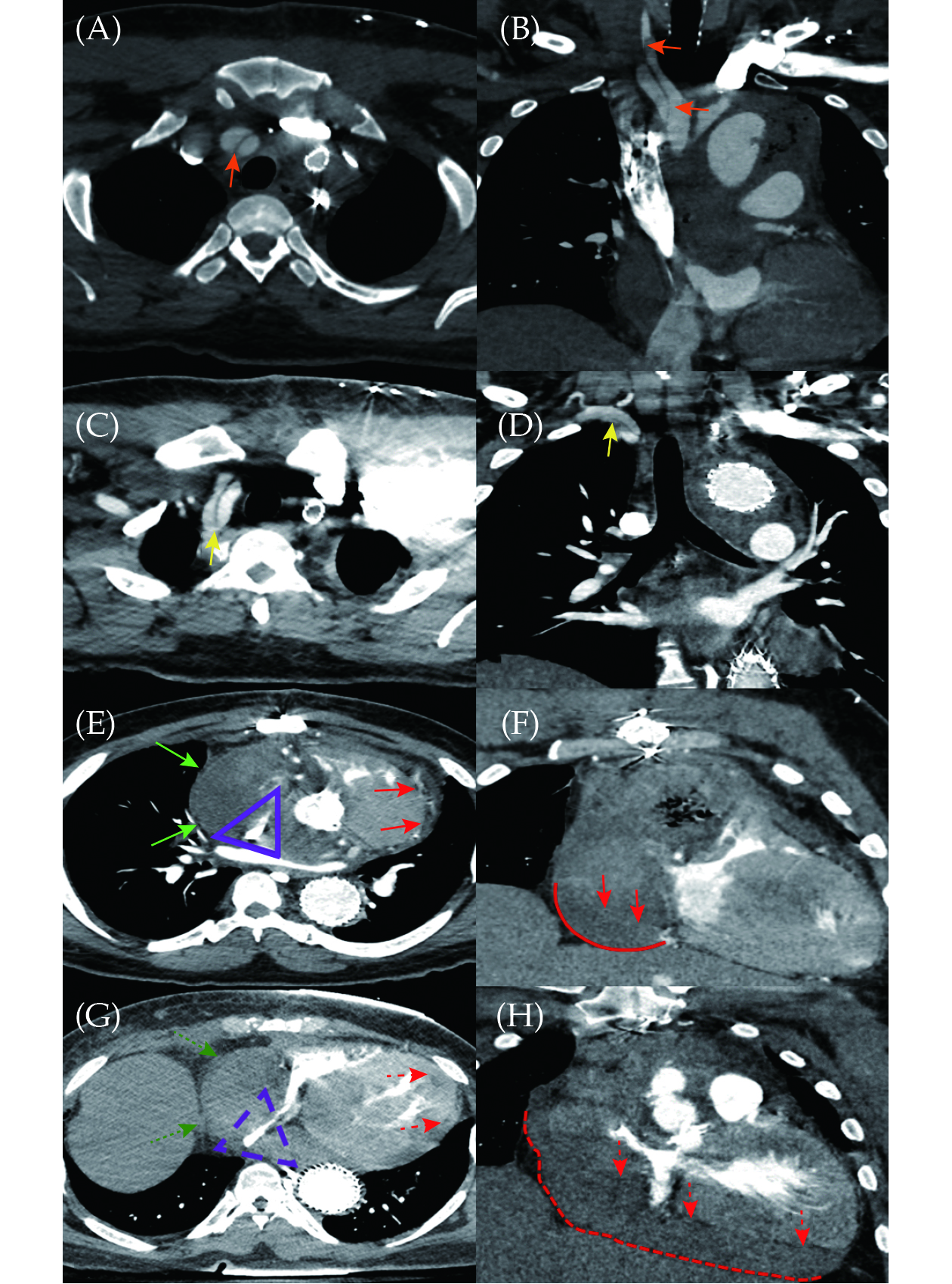

A 61-year-old African American male with a recent history of acute type A aortic dissection requiring surgical management presented to the emergency room with chest pain after cocaine use. His vital signs on arrival included a blood pressure of 147/89 mmHg, heart rate of 118 beats/min and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. Clinically the patient reported ongoing chest discomfort. Past medical history revealed a recent type A aortic dissection with repair of aortic arch with gelweave graft, aortic arch debranching with aorto to innominate bypass and aorto to left carotid bypass using a 12 mm × 8 mm trifurcate arch graft and aortic valve replacement with 23 mm On-X valve, two weeks prior to presentation. Additional relevant history included prior thoracic endovascular aortic repair, chronic kidney disease stage 2, cerebrovascular accident, hypertension and cocaine use disorder. His complete blood count and a comprehensive metabolic panel were similar to his baseline, with an international normalized ratio of 1.1. On admission, differential diagnoses included cocaine induced coronary vasospasm versus ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. With his recent history of type A aortic dissection requiring surgical repair, differentials also included aortic dissection versus pulmonary embolus versus pericarditis versus aortic aneurysm prompting urgent computed tomography angiography imaging on admission. Electrocardiogram revealed no evidence of ischemia and cardiac biomarkers were negative. Computed tomography angiography dissection was subsequently performed and revealed a large mediastinal fluid collection with internal locules of air concerning for an infective post-surgical hematoma, which severely compressed the right atrium (Figure 1). The patient was subsequently admitted for computed tomography (CT)-guided percutaneous drain placement by the interventional radiology team. Successful cardiac drain was placed with 60 mL of thick, dark sanguineous fluid aspirated for culture. Follow-up transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a massive space occupying thrombus posterior to and abutting the right atrium with mass effect on the atrium severely impairing tricuspid valve function and right ventricular filling (Figure 2). The patient underwent a right anterior thoracotomy with pericardial window for hematoma evacuation. His postoperative course remained uneventful and he was discharged on warfarin anticoagulation with home health care and cardiac rehabilitation tentatively scheduled.

However, five days after discharge, the patient was brought to the emergency room after being found collapsed at home. An emergent CT dissection revealed a non-enhancing mediastinal and pericardial density exerting significant mass effect on the right atrium and right ventricle as well as the superior and inferior vena cava. The new collection was significantly more enlarged compared to prior studies with mass effect on the right heart representing cardiac tamponade. The patient endorsed continued cocaine use after recent discharge, suspected to be the likely etiology of his recurrence. Warfarin anticoagulation was reversed and the patient underwent emergent pericardial drain placement by interventional radiology. The patient progressed to cardiac arrest soon thereafter and was taken to the operating room emergently, however, despite clot evacuation and continued chest compressions, the patient expired.

The development of a post-operative mediastinal hematoma after open heart surgery carries a high morbidity and mortality.[1] The risk of hematoma formation significantly increases in the setting post-operative anticoagulation use.[2,3] Notably, the use of cocaine in the post-operative period, can result in a hypertensive emergency, causing further mediastinal bleeding and hematoma development.[4] This could ultimately lead to the development of post-operative cardiac tamponade, defined by pericardial fluid accumulation under pressure, causing diminished cardiac filling and hemodynamic instability.

Post-operative cardiac tamponade is life threatening and requires a high index of suspicion for diagnosis and requires prompt intervention.[3] The incidence of post-operative cardiac tamponade has been reported to range from 0.1% to 6% and can occur as late as two weeks to six months following surgery.[5] Leiva, et al.[3] report a mortality rate as high as 11% in these patients. Post-operative cardiac tamponade often requires surgical re-intervention, which was shown to be associated with a 50% in-hospital mortality in another study.[6]

Cardiac tamponade can be diagnosed clinically, along with the aid of non-invasive testing such as electrocardiogram, echocardiography (ECHO) and CT. Two-dimensional ECHO remains the standard imaging of choice for diagnosis.[7] There are various features of cardiac tamponade on two-dimensional ECHO, some of which include right atrial collapse in late diastole, right ventricular wall collapses in early diastole and a dilated inferior vena cava with no inspiratory collapse. Post-operative tamponade has been reported to have distinctive findings on ECHO when compared to other causes of tamponade, which include smaller, posteriorly loculated pericardial effusions with left ventricular posterior wall motion abnormality and left ventricular diastolic collapse.[8,9] The utility of ECHOs in the early diagnosis of cardiac tamponade cannot be overemphasized. It has been suggested that the implementation of a routine ECHO protocol in the weeks following open heart surgery could lead to prompt recognition of cardiac tamponade, thereby decreasing morbidity and mortality.[3] Nevertheless, the use of CT imaging for prompt diagnosis can be a reliable and rapid alternative pending ECHO, as was done in our patient, or a supplement to ECHO when additional imaging is necessary.[6] Notable features of cardiac tamponade on CT include pericardial effusion with compression of the heart chambers, superior and inferior vena cavae and bowing of the interventricular septum.

Cardiac tamponade is an emergency and is usually managed with urgent pericardiocentesis. However, post-operative tamponade following open heart surgery, particularly when caused by a mediastinal hematoma, should be treated as a surgical emergency by mediastinal decompression and open exploration if necessary.[10] Mediastinal drainage in these cases have been shown to be ineffective for long term management.[10]

The development of a mediastinal hematoma after open heart surgery carries significant morbidity and mortality. Post-operative use of anticoagulation and recreational cocaine significantly increases the risk of hematoma formation. Additionally, while a relationship between cocaine and anticoagulant use has not been clearly established, cocaine-induced arterial thrombosis is a reported adverse effect that may imply an antagonistic effect between the two.[11] A high index of suspicion is warranted for early diagnosis as unrecognized development of cardiac tamponade carries a significantly increased risk of mortality.

All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

| [1] |

Czer LS. Mediastinal bleeding after cardiac surgery: etiologies, diagnostic considerations, and blood conservation methods. J Cardiothorac Anesth 1989; 3: 760−775. doi: 10.1016/S0888-6296(89)95267-8

|

| [2] |

Fraser DG, Ullyot DJ. Mediastinal tamponade after open-heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1973; 66: 629−631. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)40601-6

|

| [3] |

Leiva EH, Carreño M, Bucheli FR, et al. Factors associated with delayed cardiac tamponade after cardiac surgery. Ann Card Anaesth 2018; 21: 158−166. doi: 10.4103/aca.ACA_147_17

|

| [4] |

Shimokawa S, Watanabe S, Sakasegawa K, et al. Ruptured thymoma causing mediastinal hemorrhage resected via partial sternotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2001; 71: 370−372. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02234-7

|

| [5] |

Ofori-Krakye SK, Tyberg TI, Geha AS, et al. Late cardiac tamponade after open heart surgery: incidence, role of anticoagulants in its pathogenesis and its relationship to the postpericardiotomy syndrome. Circulation 1981; 63: 1323−1328. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.63.6.1323

|

| [6] |

Floerchinger B, Camboni D, Schopka S, et al. Delayed cardiac tamponade after open heart surgery: is supplemental CT imaging reasonable? J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 8: 158. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-8-158

|

| [7] |

Price S, Prout J, Jaggar SI, et al. ‘Tamponade’ following cardiac surgery: terminology and echocardiography may both mislead. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004; 26: 1156−1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.08.020

|

| [8] |

D’Cruz IA, Kensey K, Campbell C, et al. Two-dimensional echocardiography in cardiac tamponade occurring after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985; 5: 1250−1252. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80033-4

|

| [9] |

Chuttani K, Pandian NG, Mohanty PK, et al. Left ventricular diastolic collapse. An echocardiographic sign of regional cardiac tamponade. Circulation 1991; 83: 1999−2006. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.1999

|

| [10] |

Ellison LH, Kirsh MM. Delayed mediastinal tamponade after open heart surgery. Chest 1974; 65: 64−66. doi: 10.1378/chest.65.1.64

|

| [11] |

Sharma T, Kumar M, Rizkallah A, et al. Cocaine-induced thrombosis: review of predisposing factors, potential mechanisms, and clinical consequences with a striking case report. Cureus 2019; 11: e4700. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4700

|