| Citation: | Miquel Gual, Ariza Albert-Solé, Marí Garcaí Maárquez, Cristina Fernández, José L Bernal, Francesc Formiga, María-Isabel Barrionuevo, José C Sánchez-Salado, Victòria Lorente, Júlia Pascual, Isaac Llaó, Oriol Alegre, Angel Cequier, Javier Elola. Diabetes mellitus, revascularization and outcomes in elderly patients with myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock[J]. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology, 2020, 17(10): 604-611. DOI: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2020.10.006 |

The progressive ageing of population is leading to an increase in the number of elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS), which are at higher risk for complications and spending of healthcare resources.[1] The information about prognostic factors in these patients is scarce.[2] While an association between diabetes mellitus (DM) and poorer outcomes in ACS patients has been described, [3-9] the prognostic role of DM in ACS at older ages remains controversial.[10-12]

On the one hand, cardiogenic shock (CS) is a severe clinical condition that commonly leads to a high mortality, especially in elderly patients. CS is the leading cause of in-hospital mortality in patients with myocardial infarction (MI).[13, 14] Patients at older ages with MI are also at increased risk of CS.[15] Recent data suggest better outcomes in CS patients with MI treated at high complexity centers with intensive cardiac care unit (ICCU).[16] Only few studies have reported outcomes of elderly patients with MI complicated by CS (MI-CS).[17-19] Little information exists about the contribution of revascularization and ICCU management in the prognosis of elderly patients with MI-CS. On the other hand, while an association between DM and poorer outcomes in CS patients has been described, [20, 21] information about this association in elderly patients is scarce.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of DM and its prognostic impact according to age in a large series of non-selected patients with MI-CS. We also aimed to analyze the role of ICCU management and revascularization on in-hospital mortality in MI-CS patients at older ages.

We performed an observational retrospective study including patients with MI-CS. Anonymous standard data were obtained from the Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS), an administrative database that includes both demographic and clinical information of all patients discharged from all public hospitals affiliated to the SNHS, which covers 98.4% of the Spanish population. Diagnosis and procedures were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).[22] The quality of these data in patients with ACS has been previously validated.[23]

The study population included patients aged between 18 and 94 years who were discharged (death or alive) between January 2003 and December 2015 from the hospitals of the SNHS with a principal or secondary diagnosis code of ST- segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (410.*1, except 410.71) and a principal or secondary diagnosis code of CS (785.51) (MI-CS). DM presence was identified by different secondary diagnosis codes (supplemental material, Table 1S). The population was stratified in seven age groups and also in < 75 years and > 74 years. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was identified by ICD-CM procedure codes: 00.66, 36.01, 36.02, 36.05, 36.06 and 36.07; and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) by 36.10-36.19 codes.

To improve data consistency and quality, episodes with discharge at home in less than one day, discharge against medical advice or unknown disposition at discharge were excluded, as well as those classified within the major diagnostic category 14 (pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium) of the All Patient Refined Diagnostic-Related Groups.[24] To avoid duplications, discharges to other hospitals were only excluded when was not possible to identify final treating center. Clinical results in transferred patients were assigned to the center from which the patient was finally discharged.

The main clinical outcome measure was all-cause in- hospital mortality. We analyzed the effect of age and the presence of DM on in-hospital mortality in MI-CS patients, and also the association between in-hospital mortality of these patients and the availability of cardiology related resources in the hospitals where the patients were treated. Hospital admittance rate was defined as number of discharges of the study population by 100, 000 inhabitants at year.

Hospitals were classified according to the availability of cardiology related resources using the RECALCAR criteria[25] (supplemental material, Table 2S). This information was only available for the period 2005-2015. Additionally, the availability of an ICCU was obtained from the survey conducted by the Working Group on Ischemic Heart Disease and Acute Cardiovascular Care of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.[26] Criteria for the definition of ICCU included: (1) comprehensive critically-ill patient management capability, including those requiring invasive mechanical ventilation; and (2) administrative adscription of the ICCU to the cardiology department.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are expressed as n (%). The risk-standardized in-hospital mortality ratio (RSMR) was defined as the ratio between predicted mortality (which individually considers the performance of the hospital where the patient is treated) and expected mortality (which considers a standard performance according to the average of all hospitals) multiplied by the crude rate of mortality. RSMR was calculated using multilevel risk adjustment models developed by the Medicare and Medicaid Services, [27] adapted to the structure of the MBDS database, considering both inter-hospital variability and clinical and demographic variables.[28-30] Secondary diagnoses were included in groups of risk factors as described by Pope, [31] updated each year by the Agency for Health Research and Quality and including the Charlson index into the risk factors analysis.[32, 33] For the adjustment model comorbidities with odds ratio (OR) > 1 were considered. All factors entered into the final model and their coefficients were calculated from our data. Levels of significance for selecting and eliminating risk factors were P < 0.05 and P ≥ 0.10, respectively.

Calibration of models was assessed by calculating risk deciles of in-hospital mortality observed and expected obtained by the logistic multilevel model. In order to evaluate the goodness of fit, a significant decrease in the statistical likelihood ratio test compared to the null model was tested. Discrimination of models was assessed by calculating the receiver operating characteristics curves and their corresponding area under the curve (AUROC). RSMR was used to compare outcomes among groups of patients (age and DM status) and between hospitals with different characteristics according to the availability of cardiologic resources. To assess the impact of DM on in-hospital mortality and to control patient selection bias of patients between both groups, we used propensity score matching from the risk-adjusted model according to CMS, with the option of the k-nearest neighbors, a caliper of 0.05 without replacement, obtaining the average effect in the treated (ATT) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

The association between in-hospital mortality and the characteristics of hospitals was analyzed by considering the performance of PCI and CABG during the episode of hospitalization or the existence of an ICCU as independent variables in the multilevel logistic regression models or by Student's t-test or ANOVA test, when appropriate. The analysis of the impact of ICCU on mortality was performed taking into account only type 3 and type 4 hospitals.[25]

Temporal trends for in-hospital mortality during the observed period were modeled using Poisson regression analysis with year as the only independent variable. In all models, incidence rate ratios (IRR) and their 95% CI were calculated. All contrasts were bilateral, and the differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. OR and their corresponding 95% CI were also calculated. All analyses were performed with Stata 13.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas) and SPSS. 20 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

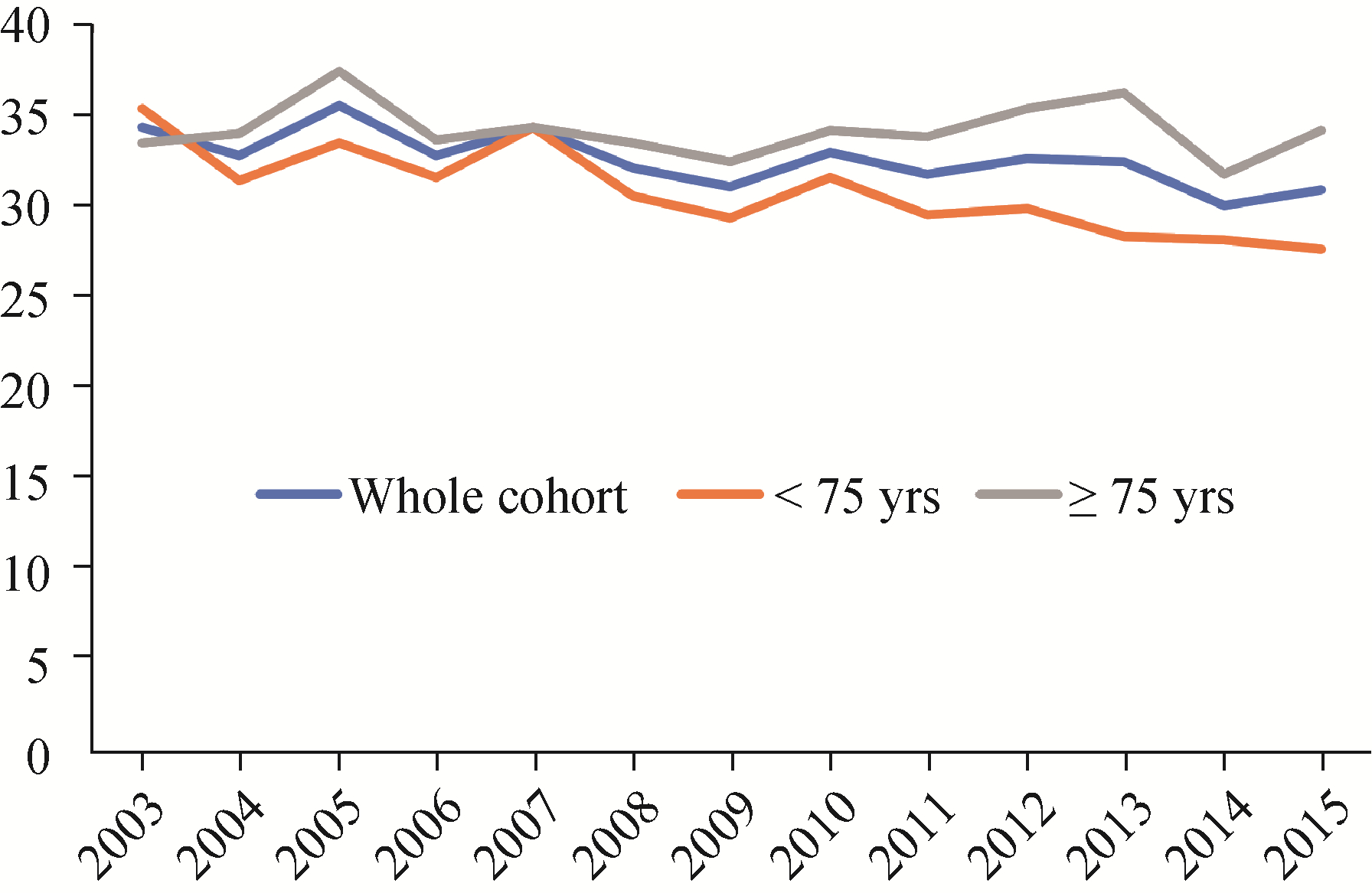

A total of 379, 041 STEMI episodes were identified across the study period. Mean age was 67.4 ± 14.2 years, and 36.3% were aged ≥ 75 years. From all STEMI episodes, 23, 590 (6.2%) had MI-CS, and 7, 724 (32.7%) of them had also DM. DM was significantly more common among MI-CS patients ≥ 75 years (34.3% vs. 24.9%, P < 0.001). A slight but significant trend to a reduction in the prevalence of DM was observed among patients MI-CS (34.4% in 2003 vs. 31% in 2015, IRR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.987-0.996, P < 0.001). While in younger patients, this trend was also observed (IRR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.98-0.99, P < 0.001), non- significant changes were observed among patients aged ≥ 75 years (IRR = 1, 95% CI: 0.99-1, P < 0.735) (Figure 1).

Among patients with MI-CS, patients with DM were significantly older and had a greater proportion of women. These patients had also a higher burden of comorbidities such as hypertension, vascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or renal failure (Table 1). Diabetic patients had been more commonly treated with revascularization procedures before the admission for MI-CS. These findings were observed both in young and in elderly patients (Table 2).

| Characteristics | MI-CS patients | ||

| Without DM (n = 15, 866) | With DM (n = 7, 724) | P-value | |

| Age, yrs | 72.4 ± 13.1 | 74.2 ± 10.3 | < 0.001 |

| Woman | 35.4% | 44.9% | < 0.001 |

| Icharlson | 6.5 ± 2.8 | 7.7 ± 3.0 | < 0.001 |

| History of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty | 7.1% | 8.0% | 0.013 |

| History of coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 4.6% | 2.4% | < 0.001 |

| Metastatic cancer, acute leukemia and other severe cancers | 1.3% | 0.9% | 0.018 |

| Protein-calorie malnutrition | 0.7% | 0.3% | < 0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1.3% | 1.5% | 0.251 |

| Dementia or other specified brain disorders | 4.4% | 4.9% | 0.100 |

| Major psychiatric disorders | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.519 |

| Hemiplegia, paraplegia, paralysis and functional disability | 2.5% | 5.0% | < 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 99.5% | 99.5% | 0.785 |

| Other cardio-respiratory failure and shock | 36.3% | 31.3% | < 0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 40.5% | 42.5% | 0.003 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 17.3% | 12.9% | < 0.001 |

| Unstable angina and other acute ischemic heart disease | 4.8% | 5.1% | 0.374 |

| Coronary atherosclerosis or angina | 52.6% | 53.8% | 0.083 |

| Valvular and rheumatic heart disease | 16.4% | 15.0% | 0.006 |

| Hypertension | 35.8% | 53.8% | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 2.1% | 1.6% | 0.010 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.8% | 3.5% | 0.004 |

| Vascular disease and complications | 7.1% | 10.9% | < 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 7.7% | 11.3% | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 8.1% | 5.2% | < 0.001 |

| Renal failure | 28.6% | 31.3% | < 0.001 |

| Trauma or other injuries | 8.6% | 6.3% | < 0.001 |

| Crude mortality rate | 70.8% | 76.2% | < 0.001 |

| Hospital stay, days | 11.4 ± 19.4 | 8.7 ± 12.3 | < 0.001 |

| Data are presented as means ± SD or %. DM: diabetes mellitus; MI-CS: myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock. | |||

| Characteristics | < 75 yrs (n = 11, 143) | ≥ 75 yrs (n = 12, 447) | P-value | |||||||

| Without DM | With DM | Without DM | With DM | |||||||

| Age, yrs | 61.6 ± 9.9 | 65.1 ± 7.7 | 82.5 ± 5.2 | 81.6 ± 4.8 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Woman | 22.5% | 33.0% | 47.5% | 54.6% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Charlson index | 6.6 ± 2.6 | 7.8 ± 3.0 | 6.5 ± 2.9 | 7.6 ± 3.1 | < 0.001 | |||||

| History of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty | 8.8% | 10.5% | 5.5% | 6.0% | < 0.001 | |||||

| History of coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 6.7% | 3.8% | 2.6% | 1.3% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Hypertension | 29.6% | 51.9% | 41.7% | 55.3% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Vascular disease and complications | 7.5% | 12.9% | 6.6% | 9.2% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8.3% | 13.4% | 7.2% | 9.7% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Pneumonia | 10.6% | 6.4% | 5.8% | 4.3% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Renal failure | 25.5% | 29.7% | 31.5% | 32.5% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Trauma or other injuries | 11.7% | 8.0% | 5.8% | 4.9% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Tuberculous meningitis | 59.3% | 67.7% | 81.5% | 83.1% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Estancia media | 14.9 ± 22.3 | 11.0 ± 14.6 | 8.1 ± 15.4 | 6.8 ± 9.5 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Data are presented as means ± SD or %. DM: diabetes mellitus; MI-CS: myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock. | ||||||||||

Among all MI-CS patients, crude mortality rate was 72%, with a significant decrease along the study period (82% in 2003 vs. 67.5% in 2015, IRR = 0.98, P < 0.001). Mortality was significantly higher among older patients (82.1% vs. 61.9%, P < 0.001). Crude mortality rate diminished significantly along the period in both age subgroups (young patients: IRR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.97-0.98, P < 0.001; elderly patients: IRR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.99-0.99, P < 0.001).

Among all MI-CS patients, the presence of DM was associated to a higher crude mortality rate (76.2% vs. 70.8%, P < 0.001). A significant reduction of crude mortality was observed across the study period both in diabetic patients (81% in 2003 vs. 61.3% in 2015, IRR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.98-0.98, P < 0.001) and patients without DM (83.8% in 2003 vs. 72.4% in 2015, IRR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98-0.99, P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

DM was independently associated to a higher mortality in the whole cohort (OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.1-1.25). The predictive model for in-hospital mortality showed an acceptable discriminative ability (AUROC = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.70-0.72) (supplemental material, Table 3S & Figure 1S) and calibration (P < 0.001). The propensity score analysis also showed a higher mortality risk among patients with DM (ATT: 0.76 vs. 0.73, OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.12-1.3, χ2 = 26, P < 0.001).

The impact of DM on in-hospital mortality was different among age subgroups. Among elderly patients, the mortality predictive model showed a less significant effect of DM as compared to the whole MI-CS cohort (OR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.03-1.26). In the propensity score analysis, these differences were even more evident. While in younger patients, DM was associated to a higher mortality risk (0.52 vs. 0.47, OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.06-1.18, χ2 = 16.8, P < 0.001), this association became non-significant in patients at older ages (0.76 vs. 0.81, OR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94-1, χ2 = 2.8, P = 0.09).

The proportion of elderly patients treated at hospitals with revascularization facilities (type 3 and type 4 hospitals) increased during the study period from 54.6% in 2005 to 77.3% in 2015 (IRR = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.02-1.04, P < 0.001). Among patients treated at type 3 or type 4 hospitals, a total of 2, 374 were admitted in hospitals with ICCU available.

Among elderly MI-CS patients treated at hospitals with revascularization facilities (n = 3, 206), 46.1% underwent revascularization (PCI or CABG) during the admission. The performance of revascularization procedures was more common in hospitals with ICCU (51.5% vs. 43.2%, P < 0.001). Diabetic patients were less often admitted to hospitals with ICCU (34.2% vs. 39.1%, P = 0.002) and underwent less often revascularization procedures as compared to the rest (43.1% vs. 47.6%, P < 0.001).

Adjusted mortality rate of MI-CS aged ≥ 75 years was lower in patients undergoing revascularization (74.9% vs. 77.3%, P < 0.001) and in patients admitted to hospitals with ICCU (adjusted mortality rate: 74.2% vs. 77.7%, P < 0.001).

Main findings from the present study are: (1) about one third of these series of non-selected MI-CS patients had previous DM, and this proportion was even higher among the elderly; (2) DM was associated with a higher mortality in the whole MI-CS cohort, but its prognostic impact was lower in patients aged ≥ 75 years; (3) diabetic patients with MI-CS were less commonly treated at hospitals with ICCU; and (4) both the performance of revascularization procedures and the availability of ICCU were associated with better outcomes in these elderly MI-CS patients.

DM is a common condition in patients with ACS, and is commonly associated to advanced age, a higher burden of comorbidities and a lower likelihood of an invasive strategy during the admission. While the prognostic impact of DM in young ACS patients is beyond doubt, conflicting data exists in patients at older ages.

Savonitto, et al.[10] assessed a prospective cohort of 645 ACS patients aged ≥ 75 years. Patients had a mean age of 81.6 years and the prevalence of DM was 35.9%. DM was associated with higher prevalence of comorbidities and lower ejection fraction and hemoglobin levels. In that study, diabetic patients had greater risk of one-year mortality (23.4% vs. 15.9%), although this association was not statistically significant after adjusting for confounder factors. In a more recent paper, [11] a large series of 12, 792 STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI was assessed, of whom 3, 023 (23.6%) were aged ≥ 75 years. Like in the paper from Savonitto, et al., [10] older patients had higher prevalence of comorbidities, a more extensive coronary artery disease and significant delay to reperfusion. DM was associated with higher 30-day mortality both in young and in elderly patients. However, after adjusting for potential confounders, this association remained significant in young patients (OR = 1.47, P = 0.047), but non-significant in the elderly (OR = 1.14, P = 0.43). In another recent study, [12] including 532 octogenarian patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS, the association between DM and outcomes was also non-significant after adjusting for confounders.

The prognostic role of DM in patients with CS remains also controversial. In a series of 443 patients with MI-CS, Lindholm, et al.[20] described a similar mortality both at 30-days and at 5-year according to DM status (diabetic: 30-day 63%, 5-year 91%; non-diabetic: 30-day 62%, 5-year 86%; P > 0.05). In contrast, in a recent study assessing 72, 765 patients admitted for MI-CS, Echouffo-Tcheugui, et al.[21] described a slightly increased mortality in patients with DM (37.9% vs. 36.8%, P < 0.001). In addition, among survivors, patients with DM had a longer hospital stay and were more likely to be discharged to a skilled nursing home. To the best of our knowledge, no study assessed the prognostic impact of DM according to age in patients with MI-CS. This is a clinically relevant issue, since mortality in patients with CS remains unacceptably high and the continuous ageing of population is increasing the number of elderly patients with different forms of cardiovascular diseases, including MI-CS.

Data from this study showed a differential impact of DM according to age, with a significantly lower effect among older patients. Despite the huge sample size, the impact of DM on mortality in elderly patients was only borderline significant. The source for this study is an administrative database, with several non-assessed potential confounders. Therefore, the impact of DM on mortality at older ages might be mostly due to their higher burden of comorbidities rather than DM itself, as described in previous studies.[10, 11]

However, the information about the potential impact of being treated by trained cardiologists in an ICCU is scarce. In a recent study, Na, et al.[34] assessed prognosis of 513 patients with CS admitted to an ICCU before and after changing from a low-intensity to high-intensity staffing unit managed by a dedicated cardiac intensivist. The authors found a significant reduction in mortality in the ICCU (from 30.6% to 17.6%, P < 0.001). Likewise, a significant reduction in mortality was observed for the subgroup of CS patients treated with extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation. More recently, Sánchez-Salado, et al.[16] analyzed an extensive series of 19, 963 discharge episodes with diagnosis of STEMI-related CS from the MBDS of the Spanish National Health System, the same source as used in our paper. Centers were classified according to ICCU availability. Interestingly, ICCU availability was associated with lower adjusted mortality rates (65.3% vs. 72%, P < 0.001). These studies included younger populations than ours (mean age was 67 years in both cases), [16, 34] and no specific analysis were performed in elderly patients. To our knowledge, no study analyzed the potential contribution of being treated in the ICCU in elderly patients with MI-CS.

Data from our study confirmed a significantly lower mortality in elderly MI-CS patients treated at hospitals with ICCU, as observed in the whole series by Sánchez-Salado, et al.[16] This benefit might be at least in part to factors such as a higher expertise among physicians currently managing these units (especially regarding tools such as pulmonary artery catheterization, implant of temporary pacemakers, echocardiography or mechanical support devices). However, to our judgment, the most important factor might be the higher proportion of patients undergoing revascularization in centers with ICCU. An early revascularization is clearly recommended in patients with MI-CS.[35] However, patients at older ages are often excluded from clinical trials and there is less information about the real impact of PCI in elderly patients with MI-CS. Dzavik, et al.[17] compared clinical factors management and outcomes according to age of the patients in the SHOCK Trial Registry (n = 588, aged < 75 years; and n = 277, aged ≥ 75 years). After exclusion of early deaths and covariate adjustment, the performace of an early revascularization was associated to a lower mortality both in young and in elderly patients. More recently, Aissaoui, et al.[18] analyzed a series of 10, 610 patients form the FAST-MI programme, of whom 3, 389 were aged ≥ 75 years, and 9.9% developed CS. The authors described an increase in the rate of PCI and an improvement in medical therapy among elderly patients, along with a reduction in one-year mortality by 32% in these patients. Rogers, et al.[19] performed a meta-analysis including twelve studies reporting short-term mortality and five studies reporting intermediate-term mortality in elderly patients with MI-CS. In that study, the authors described a lower short-term and intermediate-term mortality among elderly patients with MI-CS undergoing emergent revascularization.

Consistently with these data, data from our series showed, at a national level, a significantly lower adjusted mortality among elderly patients with MI-CS undergoing revascularization. This is a crucial issue, since in routine clinical practice, a significant proportion of elderly ACS patients are commonly denied ICU admission, and are transferred to complex centers for revascularization due to perception of short life expectancy.[36] Importantly, this is a continuously growing group of patients since them are at high risk for CS and other MI complications. Interestingly, the proportion of patients undergoing revascularization was higher in academic hospitals with ICCU.

However, it is important to note that despite current recommendations of a remarkably low proportion of MI-CS patients from this series underwent revascularization, especially at older ages.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, it has all the limitations of retrospective analyses, based on administrative data. However, the use of administrative records to estimate outcomes in health services has been validated by comparing them with data from the medical records, [22, 37] and has been applied to research on health service outcomes.[38] In contrast to the methodology used by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services, [27, 37] we did not measure 30-day mortality but in-hospital mortality. Additionally, secondary diagnoses as potential confounders could have been present at admission or during the admission.[37] We did not assess neither the "severity" of DM diagnosis (i.e., time from DM onset to heart failure at when first admission DM-related complications or type and intensity of DM therapies used), nor the impact of DM clinical management and control strategies during index admission. Finally, we cannot exclude the presence of unmeasured confounding factors that may adversely impact prognosis.

Despite these limitations, we believe that this study retrieves interesting and novel data about clinical the prognostic role of DM in one of the largest series of non-selected elderly patients with MI-CS from routine clinical practice, and the potential impact of characteristics of treating centers on outcomes in this setting. Improving risk stratification and clinical management of these very complex patients might lead to important economic and social consequences.

In conclusion, a significant proportion (32.7%) of non- selected patients with MI-CS had previous DM, and this proportion was even higher among the elderly. Prognostic impact of DM was different according to age, with a significantly lower impact at older ages. Both the availability of ICCU and the performance of revascularization procedures were associated with better outcomes in these elderly patients with MI-CS.

This study was supported by the Fundación Interhospitalaria para la Investigación Cardiovascular and Laboratorios Menarini S.L. (RECALCAR Project). All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors thank the Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare for the help provided to the Spanish Society of Cardiology to develop the RECALCAR study, with special gratitude to the General Directorate of Public Health, Quality, and Innovation.

| [1] |

Dégano IR, Elosua R, Marrugat J. Epidemiology of acute coronary syndromes in Spain: estimation of the number of cases and trends from 2005 to 2049. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2013; 66: 472-481. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2013.01.019

|

| [2] |

Krumholz HM, Gross CP, Peterson ED, et al. Is there evidence of implicit exclusion criteria for elderly subjects in randomized trials? Evidence from the GUSTO-1 study. Am Heart J 2003; 146: 839-847. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00408-3

|

| [3] |

Noman A, Balasubramaniam K, Alhous MHA, et al. Mortality after percutaneous coronary revascularization: prior cardiovascular risk factor control and improved outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2017; 89: 1195-1204. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26882

|

| [4] |

De Servi S, Crimi G, Calabrò P, et al. Relationship between diabetes, platelet reactivity, and the SYNTAX score to one-year clinical outcome in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention 2016; 12: 312-318. doi: 10.4244/EIJV12I3A51

|

| [5] |

Piccolo R, Franzone A, Koskinas KC, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on frequency of adverse events in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2016; 118: 345-352. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.05.005

|

| [6] |

Cordero A, López-Palop R, Carrillo P, et al. Comparison of long-term mortality for cardiac diseases in patients with versus without diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2016; 117: 1088-1094. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.12.057

|

| [7] |

Kuhl J, Jörneskog G, Wemminger M, et al. Long-term clinical outcome in patients with acute coronary syndrome and dysglycaemia. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015; 14: 120. doi: 10.1186/s12933-015-0283-3

|

| [8] |

Ritsinger V, Saleh N, Lagerqvist B, et al. High event rate after a first percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with diabetes mellitus: results from the Swedish coronary angiography and angioplasty registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2015; 8: e002328. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26025219

|

| [9] |

Donahoe SM, Stewart GC, McCabe CH, et al. Diabetes and mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2007; 298: 765-775. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.765

|

| [10] |

Savonitto S, Morici N, Cavallini C, et al. One-year mortality in elderly adults with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: effect of diabetic status and admission hyperglycemia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62: 1297-1303. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12900

|

| [11] |

Gual M, Ariza-Solé A, Formiga F, et al. Diabetes mellitus is not independently associated with mortality in elderly patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Insights from the Codi Infart registry. Coron Artery Dis 2020; 31: 1-6. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000821

|

| [12] |

Gual M, Formiga F, Ariza-Solé A, et al. Diabetes mellitus, frailty and prognosis in very elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019; 31: 1635-1643. doi: 10.1007/s40520-018-01118-x

|

| [13] |

Aissaoui N, Puymirat E, Tabone X, et al. Improved outcome of cardiogenic shock at the acute stage of myocardial infarction: a report from the USIK 1995, USIC 2000, and FAST-MI French nationwide registries. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2535-2543. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs264

|

| [14] |

Hochman JS, Buller CE, Sleeper LA, et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction--etiologies, management and outcome: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock? J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 1063-1070. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10985706?dopt=Abstract

|

| [15] |

Kolte D, Khera S, Aronow WS, et al. Trends in incidence, management, and outcomes of cardiogenic shock complicating ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the United States. J Am Hear Assoc 2014; 3: e000590. doi: 10.1161/jaha.113.000590

|

| [16] |

Sánchez-Salado JC, Burgos V, Ariza-Solé A, et al. Trends in cardiogenic shock management and prognostic impact of type of treating center. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2020; 73: 546-553. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2019.10.009

|

| [17] |

Dzavik V, Sleeper LA, Cocke TP, et al. Early revascularization is associated with improved survival in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 828-837. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00844-8

|

| [18] |

Aissaoui N, Puymirat E, Juilliere Y, et al. Fifteen-year trends in the management of cardiogenic shock and associated 1-year mortality in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: the FAST-MI programme. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 1144- 1152. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.585

|

| [19] |

Rogers PA, Daye J, Huang H, et al. Revascularization improves mortality in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Int J Cardiol 2014; 172: 239-241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.311

|

| [20] |

Lindholm MG, Boesgaard S, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Diabetes mellitus and cardiogenic shock in acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail 2005; 7: 834-839. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.09.007

|

| [21] |

Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Kolte D, Khera S, et al. Diabetes mellitus and cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2018; 131: 778-786.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.03.004

|

| [22] |

Registro de altas de hospitalización: CMBD del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Glosario de términos y definiciones. Portal estadístico SNS Web site. https://pestadistico.inteligenciadegestion.msssi.es/publicoSNS/comun/DescargaDocumento.aspx?IdNodo=6415 (accessed January 16, 2018).

|

| [23] |

Bernal JL, Barrabés JA, Íñiguez A, et al. Clinical and administrative data on the research of acute coronary syndrome in Spain. Minimum Basic Data Set Validity. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2019; 72: 56-62. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2018.01.007

|

| [24] |

Averill RF, McCullough EC, Goldfield N, et al. APR-DRG Definition Manual v.31.0 2013. APR-DRG Definition Manual Web site. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/grp031_aprdrg_meth_ovrview.pdf (accessed Februar 28, 2020).

|

| [25] |

Íñiguez Romo A, Bertomeu Martínez V, Rodríguez Padial L, et al. The RECALCAR Project. Healthcare in the cardiology units of the Spanish National Health System, 2011 to 2014. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2017; 70: 567-575. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2016.12.031

|

| [26] |

Worner F, San Román A, Sánchez PL, et al. The healthcare of patients with acute and critical heart disease. Position of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016; 69: 239-242. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2015.07.018

|

| [27] |

2015 Condition: specific measures updates and specifications report hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized mortality measures. Acute Myocardial Infarction, 9th Edition; Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation (YNHHSC/CORE). Prepared For: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

|

| [28] |

Goldstein H, Spiegelhalter DJ.[League tables and their limitations: statistical aspects of institutional performance]. J R Stat Soc 1996; 159: 385-444.[In Spanish].

|

| [29] |

Normand SLT, Glickman ME, Gatsonis C.[Statistical methods for profiling providers of medical care: issues and applications]. J Am Stat Assoc 1997; 92: 803-814.[In Spanish].

|

| [30] |

Shahian DM, Normand SL, Torchiana DF, et al. Cardiac surgery report cards: comprehensive review and statistical critique. Ann Thorac Surg 2001; 72: 2155-2168. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03222-2

|

| [31] |

Pope GC, Ellis RP, Ash AS, et al. Diagnostic cost group hierarchical condition category models for medicare risk adjustment. Final report to the Health Care Financing Administration under contract number 500-95-048. Health Economics Research, Inc. Waltham, MA, USA.

|

| [32] |

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40: 373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

|

| [33] |

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hospital Standardized Mortality Ratio (HSMR) Web site. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/HSMR_hospital_mortality_trends_in_canada.pdf (accessed Februar 28, 2020).

|

| [34] |

Na SJ, Park TK, Lee GY, et al. Impact of a cardiac intensivist on mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock. Int J Cardiol 2017; 244: 220-225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.06.082

|

| [35] |

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2129-2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128

|

| [36] |

Ariza-Solé A, Alegre O, Elola FJ, et al. Management of myocardial infarction in the elderly. Insights from Spanish Minimum Basic Data Set. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2019; 8: 242-251. doi: 10.1177/2048872617719651

|

| [37] |

Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2006; 113: 1683-1692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611186

|

| [38] |

van Walraven C, Jennings A, Taljaard M, et al. Incidence of potentially avoidable urgent readmissions and their relation to all-cause urgent readmissions. CMAJ 2011; 183: E1067-E1072. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110400

|

| Characteristics | MI-CS patients | ||

| Without DM (n = 15, 866) | With DM (n = 7, 724) | P-value | |

| Age, yrs | 72.4 ± 13.1 | 74.2 ± 10.3 | < 0.001 |

| Woman | 35.4% | 44.9% | < 0.001 |

| Icharlson | 6.5 ± 2.8 | 7.7 ± 3.0 | < 0.001 |

| History of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty | 7.1% | 8.0% | 0.013 |

| History of coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 4.6% | 2.4% | < 0.001 |

| Metastatic cancer, acute leukemia and other severe cancers | 1.3% | 0.9% | 0.018 |

| Protein-calorie malnutrition | 0.7% | 0.3% | < 0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1.3% | 1.5% | 0.251 |

| Dementia or other specified brain disorders | 4.4% | 4.9% | 0.100 |

| Major psychiatric disorders | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.519 |

| Hemiplegia, paraplegia, paralysis and functional disability | 2.5% | 5.0% | < 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 99.5% | 99.5% | 0.785 |

| Other cardio-respiratory failure and shock | 36.3% | 31.3% | < 0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 40.5% | 42.5% | 0.003 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 17.3% | 12.9% | < 0.001 |

| Unstable angina and other acute ischemic heart disease | 4.8% | 5.1% | 0.374 |

| Coronary atherosclerosis or angina | 52.6% | 53.8% | 0.083 |

| Valvular and rheumatic heart disease | 16.4% | 15.0% | 0.006 |

| Hypertension | 35.8% | 53.8% | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 2.1% | 1.6% | 0.010 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.8% | 3.5% | 0.004 |

| Vascular disease and complications | 7.1% | 10.9% | < 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 7.7% | 11.3% | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 8.1% | 5.2% | < 0.001 |

| Renal failure | 28.6% | 31.3% | < 0.001 |

| Trauma or other injuries | 8.6% | 6.3% | < 0.001 |

| Crude mortality rate | 70.8% | 76.2% | < 0.001 |

| Hospital stay, days | 11.4 ± 19.4 | 8.7 ± 12.3 | < 0.001 |

| Data are presented as means ± SD or %. DM: diabetes mellitus; MI-CS: myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock. | |||

| Characteristics | < 75 yrs (n = 11, 143) | ≥ 75 yrs (n = 12, 447) | P-value | |||||||

| Without DM | With DM | Without DM | With DM | |||||||

| Age, yrs | 61.6 ± 9.9 | 65.1 ± 7.7 | 82.5 ± 5.2 | 81.6 ± 4.8 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Woman | 22.5% | 33.0% | 47.5% | 54.6% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Charlson index | 6.6 ± 2.6 | 7.8 ± 3.0 | 6.5 ± 2.9 | 7.6 ± 3.1 | < 0.001 | |||||

| History of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty | 8.8% | 10.5% | 5.5% | 6.0% | < 0.001 | |||||

| History of coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 6.7% | 3.8% | 2.6% | 1.3% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Hypertension | 29.6% | 51.9% | 41.7% | 55.3% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Vascular disease and complications | 7.5% | 12.9% | 6.6% | 9.2% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8.3% | 13.4% | 7.2% | 9.7% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Pneumonia | 10.6% | 6.4% | 5.8% | 4.3% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Renal failure | 25.5% | 29.7% | 31.5% | 32.5% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Trauma or other injuries | 11.7% | 8.0% | 5.8% | 4.9% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Tuberculous meningitis | 59.3% | 67.7% | 81.5% | 83.1% | < 0.001 | |||||

| Estancia media | 14.9 ± 22.3 | 11.0 ± 14.6 | 8.1 ± 15.4 | 6.8 ± 9.5 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Data are presented as means ± SD or %. DM: diabetes mellitus; MI-CS: myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock. | ||||||||||